Planck didn’t listen to himself, but you should

1918 Nobel Prize in Physics Revisited

As a researcher, the extent to which one is involved in a research program is inexplicable.

Being constantly engrossed in a problem results in an incorrect evaluation of the significance of the same, and hence of one’s contribution to the discipline once that problem is solved. So, the resolution of important questions by researchers changes the world to a little lesser extent than what they expect it to.

But for one man in particular, the sequence of events turned out to be on the opposite end of the spectrum. A skeptic of the transient ideas, Planck never thought much of his creation. It turned out that the end of one quest by Planck, would lead to another, one which was much bigger, deeper and hitherto unheard of.

This is a tale of when the gut feeling turns out to be something substantially more.

This is the tale of the Nobel Prize in Physics 1918 which was awarded to Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck “in recognition of the services he rendered to the advancement of Physics by his discovery of energy quanta”.

Background

The story starts from a quest for understanding the thermal electromagnetic radiation.

Specifically, the thermal electromagnetic radiation emittted by a body in thermodynamic equilibrium with its surroundings which was an important question in the field of what is now referred to as thermal physics.

Prèvost

Thermal physics of bodies can be traced back to Pierre Prèvost, who in 1791 proposed the following law :

A body emits and absorbs radiant energy at equal rates when it is in equilibrium with its surroundings. Its temperature then remains constant. If the body is not at the same temperature as its surroundings there is a net flow of energy between the surroundings and the body because of unequal emission and absorption.

This statement is known as Prévost’s Theory of Exchanges. Prévost considered that electromagnetic radiation was a fluid that he called “free heat”. Prevost’s theory of exchanges states that each body radiates to, and receives radiation from, other bodies. The radiation from each body is emitted regardless of the presence or absence of other bodies.

Following are the translated definitions of equilibria also provided by Prevost also in 1791 : Absolute equilibrium of free heat is the state of this fluid in a portion of space which receives as much of it as it lets escape. Relative equilibrium of free heat is the state of this fluid in two portions of space which receive from each other equal quantities of heat, and which moreover are in absolute equilibrium, or experience precisely equal changes.

Prevost considered that “The heat of several portions of space at the same temperature, and next to one another, is at the same time in these two species of equilibrium.”

Stewart

Next major milestone in this field was the Scottish physicist and meteorologist, Balfour Stewart’s contribution.

Stewart, in 1858, described his experiments on the thermal radiative emissive and absorptive powers of polished plates of various substances, compared to that of lamp-black surfaces at the same temperature.

He wrote in his account of some experiments on radiant heat to Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh :

“Lamp-black, which absorbs all the rays that fall upon it, and therefore possesses the greatest possible absorbing power, will possess also the greatest possible radiating power.”

He proposed that his measurements implied that radiation was both absorbed and emitted by particles of matter throughout depths of the media in which it propagated.

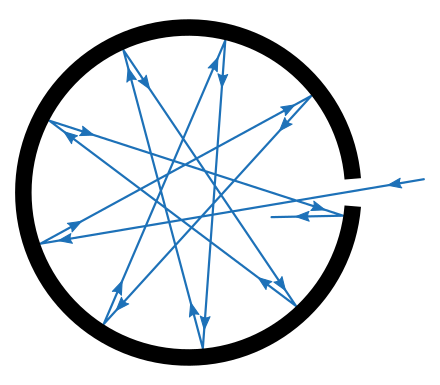

He did not, however postulate unrealizable perfectly black surfaces (which we today call black bodies). The closest he got to the concept of a black body is when he concluded that his experiments showed that in a cavity in thermal equilibrium, the heat radiated from any part of the interior bounding surface, no matter of what material it might be composed, was the same as would have been emitted from a surface of the same shape and position that would have been composed of lamp-black.

This concept is used till date and the insulated walled enclosure is used as an idealisation for the black body.

The Radiation Problem and Early Resolutions

Kirchoff

As mentioned earlier, the radiation problem had been explored experimentally by the likes of Stewart, but no theoretical treatment seemed to agreed with the observations.

The theoretical advancements pertaining to the problem only came after the German physicist Gustav Kirchhoff who, in 1859, proposed Kirchhoff’s law of Thermal Radiation which states that for a body of any arbitrary material emitting and absorbing thermal electromagnetic radiation at every wavelength in thermodynamic equilibrium, the ratio of its emissive power to its dimensionless coefficient of absorption is equal to a universal function only of radiative wavelength and temperature. That universal function describes the perfect black-body emissive power.

It is important to point out here that unlike the physicists who preceded him, Kirchoff assumed the existence of a perfect absorber/emitter. In his paper, ‘The relation between the emissivity and the absorption capacity of the bodies for heat and light’, Kirchhoff wrote :

‘The proof to be given here for the assertion is based on the assumption that bodies are conceivable which, at infinitely small thickness, completely absorb all the rays which fall upon them, and thus neither reflect nor let rays pass. I want to call such bodies ideal black, or just black. It is necessary first to examine the radiation of such black bodies.’

At the end of the paper he added,

‘Another conclusion from the proved theorem may find room here at the end. If a space is enclosed by bodies of the same temperature, and no rays can penetrate through these bodies, then each ray-bundle in the interior of the space is of its quality and intensity just as if it came from a perfectly black body of the same temperature irrespective of the nature and shape of the body and only due to the temperature. The correctness of this assertion is seen when one considers that a bundle of rays, which has the same shape and the opposite direction as the chosen one, is completely absorbed in the infinite number of reflections which it experiences on the imaginary bodies. In the interior of an opaque, glimmering body of a certain temperature, the same brightness always takes place, which may be the same in the rest.’

This statement implies that for a black body—regardless of its shape or material—if it is at a certain temperature, the radiation it emits (or absorbs) within a confined space is indistinguishable from that of any other perfectly black body at the same temperature. Essentially, a black body at a given temperature behaves in terms of radiation as if it were an idealized object that absorbs all incident radiation and emits the maximum possible amount at that temperature, hence, verifying the claim he made at the beginning of the proof.

Tiny hole in an enclosure is an idealization of a black body

(Source : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_body)

In the same year, Kirchhoff had also postulated that the intensity of the electromagnetic radiation emitted by a black body depends on the frequency of the radiation and the temperature of the body.

Thus, attempts to find intensity as an exact function of the frequency and temperature occupied the brilliant minds of the time for the latter half of the 19th century.

Wein & Rayleigh-Jeans

One of these brilliant minds was the German physicist Wilhelm Wien.

Wein had formulated a displacement law in 1893 called Wien’s displacement law, that is used to this day. It stated that the black-body radiation curve for different temperatures will peak at different wavelengths that are inversely proportional to the temperature.

\[λ_{max}T = constant\]This was an important first step in his investigations on the radiation problem, which later culminated in his discovery of Wein’s distribution law of blackbody radiation in 1896.

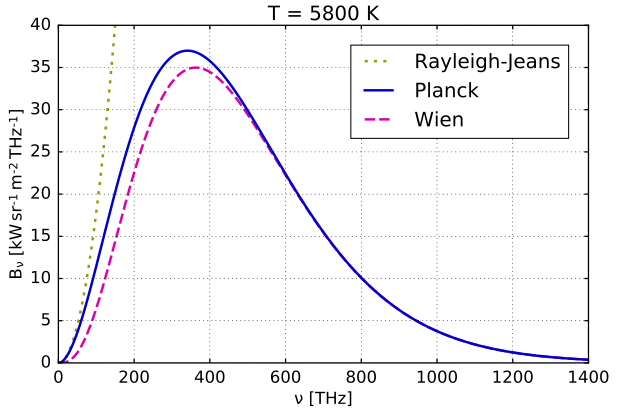

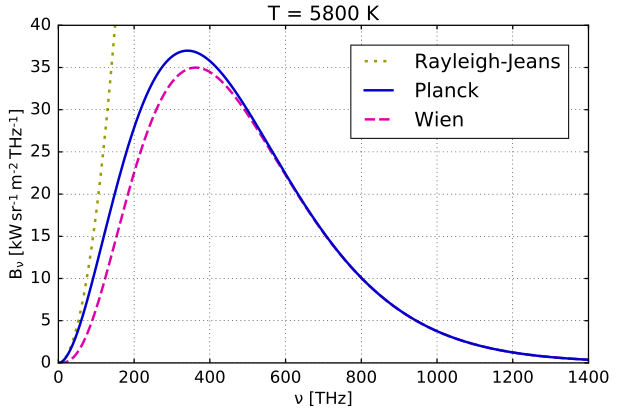

Unfortunately, Wien’s distribution law (now called Wein’s approximation) was only valid at high frequencies, and underestimated the intensity at low frequencies such as infrared radiation.

Another attempt at solving the radiation problem was the Rayleigh–Jeans law.

Wonderful agreement of this law with the experimental results at low frequencies meant that their argument (based on classical physics) was promising. But the law was pathetically incapable of any predictions near high frequencies. It predicted that an ideal black body at thermal equilibrium would emit an unbounded quantity of energy as wavelength decreased into the ultraviolet range. This conflict between observations and the predictions of classical physics is called the ultraviolet catastrophe.

Comparison of Wein and Rayleigh-Jean’s distribution laws

(Source : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rayleigh%E2%80%93Jeans_law)

Planck, an admirer of the absolutes, originally took up the blackbody problem as it was independent of atomic models or other particular hypotheses that were untested, yet prevelant at the time.

Who knew that avoiding the uncertains for the absolutes would be a turning point for Planck’s career and ironically be a fundamental step in the physics of the uncertain.

A Gut Feeling

Max Planck was a colleague of Wien who did not pay heed to empirical laws.

So, at the beginning of his work, he wanted to find a proof for Wien’s distribution formula using electromagnetism and thermodynamics. This theoretical basis for Wien’s law resulted in it becoming the Wien–Planck law.

Meanwhile, experiments by the duo Heinrich Rubens and Ferdinand Kurlbaum started to cast some doubt on Wien’s formula owing to its disagreement with the experimentally determined values at low frequencies. Rayleigh’s law did a better job of fitting these observations as compared to Wien’s.

Planck was made aware of these results by Rubens. So he tried to alter his expression for the entropy of the radiation by generalizing it. From the new expression he calculated back the emissivity and found a formula for the radiation energy, which he communicated to Rubens. That same night, Rubens and Kurlbaum checked Planck’s formula against their experimental results and found perfect agreement.

Thus, Planck had found the blackbody formula.

Regardless of the exactitude of the discovery, Planck’s derivation for the formula was heuristic as he assumed that a hypothetical electrically charged oscillator in a cavity that contained black-body radiation could only change its energy in a minimal increment, E, that was proportional to the frequency of its associated electromagnetic wave without any justification for the same.

Even Planck mentioned in his Nobel Prize address, “But even if the radiation formula proved to be perfectly correct, it would after all have been only an interpolation formula found by lucky guess-work and thus would have left us rather unsatisfied. I therefore strived from the day of its discovery, to give it a real physical interpretation and this led me to consider the relations between entropy and probability according to Boltzmann’s ideas. After some weeks of the most intense work of my life, light began to appear to me and unexpected views revealed themselves in the distance.”

Significance

Planck originally regarded the hypothesis of dividing energy into increments as a mere mathematical ‘trick’.

This ‘trick’, while he believed was to be done for the sake of interpolation, other physicists including Albert Einstein built on his work, for instance in the case of photoelectric effect, which solidified the case for Planck’s theory.

Planck’s desparation for the solution to the radiation problem led to an insight that is now considered to be of fundamental importance to the development of this quantum theory.

Just as Planck said, ‘An important scientific innovation rarely makes its way by gradually winning over and converting its opponents: What does happen is that the opponents gradually die out’.

Similarly, even the most serious objections to Planck’s theory simply died down as a result of the works of physicists who stood on the shoulders of this giant.

As a result of which we fondly remember Max Planck as the founding father of Quantum Theory.

References

- From X-Rays to Quarks by Emilio Segrè

- The relation between the emissivity and the absorption capacity of the bodies for heat and light;by Gustav Robert Kirchhoff (Ueber das Verhältniss zwischen dem Emissionsvermögen und dem Absorptionsvermögen der Körper für Wärme und Licht) [Published - Annalen der Physik Volume 185 Issue 2 pp. 275-301]

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1918/ceremony-speech/

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Planck

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_Wien

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radiative_equilibrium

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black-body_radiation